In the vibrant, smoky nightclubs of 1950s and 60s Addis Ababa, a sound would rise above the chatter, a soulful, piercing melody from a one-stringed fiddle. The crowds would hush. All eyes would turn to the stage, not to a man, the expected master of the instrument, but to a woman whose presence was as commanding as the music she played. This was Asnaketch Worku: a virtuoso, an actress, a force of nature who defied every convention to become the undisputed empress of Ethiopia’s golden age of music.

Her story is not just one of fame; it is a testament to the power of raw, untamed talent and a fierce refusal to be confined. In an era and a industry dominated by men, Asnaketch did not simply find a place to sing. She seized the instruments themselves and played her way into history.

The Sound of a Revolution

To understand Asnaketch’s revolution, you must understand the landscape. Ethiopian traditional music, particularly the zema (chant) and tizita (a genre of nostalgic ballad), was deeply respected. The instruments, the krar (lyre), the begena (a large, often sacred lyre), and the messengo (a one-string fiddle played with a bow), were traditionally the domain of male musicians, often azmaris (wandering minstrels) who performed in courts and taverns.

Asnaketch shattered this tradition. She was not formally trained; her education was the city itself. Born into a humble family, she taught herself to play the messengo and the begena with a skill that left seasoned musicians in awe. The messengo, in particular, became her signature. It is an instrument known for its difficulty, its mournful, expressive sound capable of conveying the deepest emotions of the tizita. To see a woman not only play it but master it with such passion and authority was a radical act. She wasn’t just accompanying herself; she was leading with her instrument, telling stories through its strings that were uniquely hers.

A Star is Born: The Stage and The Screen

Her talent was too immense to remain in the shadows. Asnaketch’s big break came when she was discovered by the Ethiopian National Theatre. This launched her into a dual career that cemented her icon status. On stage and in burgeoning Ethiopian cinema, she became a celebrated actress, often playing strong, charismatic roles that mirrored her own personality.

But it was in the nightclubs where her legend was truly forged. Places like the Arizona Club and the Congo Hotel became her kingdom. She would perform, her powerful voice filling the room, her fingers dancing across the messengo’s single string. She performed for Emperor Haile Selassie, a mark of the highest national acclaim. Her performances were were events. She was known for her charismatic, sometimes unpredictable stage presence, a woman fully in command of her art and her space. She sang of love, of loss, of the bittersweet nature of life (the core of tizita), with a raw honesty that resonated with a society navigating modernity.

The Queen of Tizita: A Soundtrack for Longing

To listen to Asnaketch Worku is to understand the soul of Tizita. More than just a musical genre, Tizita is a feeling, a profound, bittersweet nostalgia for a memory, a person, or a time that has passed. It is the Ethiopian blues. And Asnaketch was its undisputed queen.

Her mastery of the messengo was the key. The instrument’s mournful, wavering cry is the perfect voice for this longing. In her hands, it didn’t just play notes; it wept, it yearned, it remembered. Take one of her most iconic songs, simply titled “Tizita.” The introduction is a slow, melancholic melody from the messengo, setting a scene of quiet reflection. When her voice enters, it is not a dramatic shout but a deep, resonant confession.

But Asnaketch’s genius was in the emotion she conveyed beyond the lyrics. You don’t need to understand Amharic to feel the heartache and the sweet sorrow in her performance. The slight cracks in her voice, the pauses between phrases, the way she would lean into a note with her messengo—all of it was a masterclass in emotional storytelling. She didn’t just sing about tizita; she made the audience feel it in their bones. In the crowded nightclubs, her performances would often be met with a reverent silence, followed by explosive applause. She was giving voice to the collective memory and longing of her people.

Defying the Frame

Asnaketch’s defiance was not always expressed in words, but in her very being. In a society with defined gender roles, she lived life on her own terms. She was a single mother and a prolific artist, supporting herself entirely through her craft. She was fiercely independent, a trait that was both admired and scrutinized. She challenged what it meant to be a female artist, not just a pretty face with a voice, but a complete musician, an instrumentalist, a creator.

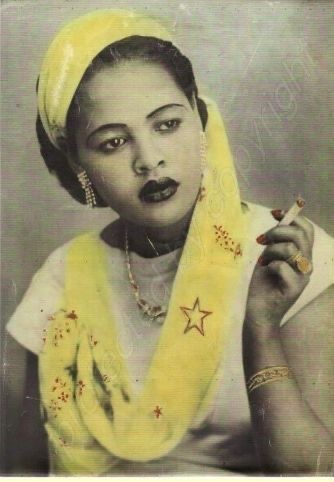

Her personal style was as distinctive as her music. She was often photographed with an intense, direct gaze, her hair styled elegantly, embodying a sophisticated, modern Ethiopian womanhood. She refused to be pigeonholed. She could move from the deep spiritual tones of the begena to the lively rhythms of popular tunes, all while maintaining her unique, authentic voice.

Her public persona was captivating, fueled by stories of her fierce independence. One famous anecdote illustrates this perfectly. It is said that during a performance for Emperor Haile Selassie at the National Palace, a setting of utmost formality, Asnaketch became so engrossed in her music that she kicked off her shoes mid-song to play with greater feeling. While some in the court were scandalized, the Emperor himself, appreciating her authentic passion, was reportedly amused and impressed. This story, whether apocryphal or not, became part of her legend—a testament to a spirit too large to be contained by protocol. Her art came first, always.

The Enduring Echo of an Empress

Asnaketch Worku’s life was pretty dramatic. Her later years were marked by challenges, and her passing in 2011 was a moment of national mourning. Yet, her legacy is experiencing a powerful revival, especially among a new generation of Ethiopian artists who see her as a beacon of authenticity.

Contemporary stars like the electric krar player and singer Mikael Seifu sample her recordings, weaving her timeless sound into their electronic compositions. Female singers cite her not just for her voice, but for her trailblazing path as an instrumentalist and a woman who owned her narrative. In a 2018 interview, popular Ethiopian singer Betty G noted, “Asnaketch showed us that a woman could be the complete package, the musician, the star, the boss. She wasn’t behind anyone.” This rediscovery is not about nostalgia; it’s about recognizing a kindred spirit whose struggle for artistic freedom resonates deeply today.

Today, a new generation of Ethiopian artists cites her as an inspiration. Musicians and music lovers, both in Ethiopia and across the diaspora, are rediscovering her recordings, marveling at her technical skill and her raw emotional power. She is no longer just a memory from a golden age; she is a model of artistic integrity and fearless self-expression.

In a world that still often tries to limit women, Asnaketch’s story is a timeless reminder. She teaches us that talent knows no gender. She shows us that the tools of art, the instruments, the stages, the stories—belong to anyone brave enough to claim them. She did not ask for permission to be great; she simply was.

Asnaketch Worku was more than a singer or an actress. She was a pioneer who carved a space for herself with the bow of her messengo. She stole the heart of a capital city not by fitting in, but by standing out, unapologetically and brilliantly. Her music remains a powerful echo of a woman who lived, loved, and created entirely on her own terms, a true empress of her own destiny.